Premature (Preterm) Infant

Overview

What is premature (preterm) birth?

Pregnancy normally lasts about 40 weeks. When delivery occurs between 20 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, it's called a preterm birth. A baby born early is called preterm (or premature). Preterm babies are sometimes called "preemies."

Why is preterm birth a problem?

When babies are born too early, their major organs aren't fully formed. As a result, preterm infants may not be able to eat, breathe, or stay warm on their own. They may also have jaundice, infection, or anemia.

What causes preterm birth?

Preterm birth can be caused by a problem with the fetus, the mother, or both. The most common causes include problems with the placenta, uterus, or cervix; pregnancy with twins or more; infection; or drug or alcohol use during pregnancy. Often the cause is never known.

What kind of treatments might a preterm infant need?

Some preterm babies may need care in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), where they can be watched closely for infections and changes in breathing and heart rate and be kept warm. They may be fed through a vein or a tube in their nose. Sick and very premature infants may need other treatments.

Does preterm birth cause long-term problems?

Most preterm babies don't develop serious long-term problems. But the earlier a baby is born, the higher the risk of later problems such as cerebral palsy or intellectual disability.

- Most babies who are born between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy do well after birth. If a baby does well after birth, the risk of long-term problems is low.

- Babies who are born before 26 weeks or who are very small— 1000 g (2.2 lb) or less—are the most likely to have long-term disability.

Work with your doctor to closely watch your baby's development and to try to catch any problems early on.

What can you expect when you take your baby home?

Your baby may be asleep or awake for shorter periods of time than you expect.

- Preterm babies sleep more than full-term infants do but for shorter periods of time.

- They are seldom awake for more than brief periods until about 2 months after their due date, so it may seem like a long time before your infant responds to your presence.

Your baby may be easily disturbed by too much light, sound, touch, or movement. If so, create a more calming environment, swaddle your infant in a blanket, and hold him or her as much as possible.

Your baby probably will come home with a feeding schedule. To avoid dehydration, never go longer than 4 hours between feedings. Small feedings may help reduce spitting up.

Your baby's doctor may recommend adding iron, vitamins, or supplemental formula to a breastfed diet. Preterm babies lack the iron stores that full-term infants have at birth.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Delivery of Your Preterm Infant

During preterm labor

A preterm birth may happen suddenly or after days or weeks of waiting. If you know you may deliver early, you can be better prepared.

During preterm labor, both you and your baby are considered high-risk. This means that you will have less freedom to move about and fewer choices about the birth.

- Monitoring.

- You'll be on constant fetal heart monitoring. The monitor will limit your movement, but it's a good way for the doctor to learn how well your baby is doing.

- You'll also be checked regularly for changes in your heart rate, body temperature, and uterine contractions.

- Medicines.

You can refuse pain medicine during preterm labor. But medicines such as antibiotics or corticosteroids can be important to ensure your infant's chances of good health after birth.

- Delivery.

You'll probably deliver vaginally. But if your health or your baby's health is at risk, you may need a cesarean section (C-section).

After your baby is born

After delivery, the neonatal staff will watch over and stabilize your preterm infant. If your baby's gestational age is less than 36 weeks, your baby may be moved to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for specialized care. The obstetric staff will care for you. This will take at least a few hours.

Learn more

Watch

Taking Care of Yourself

If your preterm baby is in the hospital, you may become overwhelmed with new emotions and information. You and your loved ones may handle issues and feelings differently, and it may create a strain on your relationships. These tips may help during this time.

- Make time for yourself.

Try to be sure you get enough rest, food, exercise, and fresh air and sunlight.

- Get as much help as you can.

Arrange for and accept help from friends and family.

- Manage your emotions.

It can help to talk with a supportive friend, a spiritual advisor, a counselor, or a social worker. It may also help to keep a journal of your thoughts and feelings.

- Join a support group.

If your hospital has a support group for NICU parents, try it out. Sometimes the best support comes from people who are going through the same issues that you are.

- Be alert for changes in your mental health.

- It's normal to have some sadness, anxiety, and mood swings after delivery. You can always call the Maternal Mental Health Hotline at 1-833-TLC-MAMA (1-833-852-6262) for support. If these mood changes last more than a couple of weeks, talk to your doctor or midwife.

Learn more

Watch

Health Problems in Preterm Newborns

When babies are born too early, their major organs aren't fully formed. This can cause health problems that require treatment in the hospital. Preterm infants may:

- Have immature lungs so they can't breathe on their own.

- Stop breathing from time to time (apnea of prematurity).

- Not be able to stay warm on their own.

- Not be able to feed by mouth.

Many preterm babies also have jaundice, infection, or anemia.

Learn more

Watch

Treatments a Preterm Infant May Need

Most infants born at 36 and 37 weeks' gestation are mature enough to go home from the hospital. But babies born earlier may need care in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), where they can be:

- Watched closely for infections and changes in breathing and heart rate.

- Kept warm in enclosed cribs called isolettes until they can maintain their body heat.

- Fed through a vein (intravenously) or through a tube in their nose, if needed. Tube-feeding continues until a baby is able to breathe, suck, and swallow and can take all feedings by breast or bottle.

Sick and very premature infants may need other treatments, depending on what problems they have. A baby who needs help breathing may have an oxygen tube or a machine, called a ventilator, that moves air in and out of the lungs. Some babies may need medicine or surgery.

Learn more

Getting to Know the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is the part of the hospital where premature or sick newborns get care.

It can be scary to see your baby in a room filled with unfamiliar machines. Some of them are noisy. But all of them help the doctor and the NICU staff take good care of your baby.

Some equipment protects and keeps your baby comfortable.

- The incubator, or isolette, is a special crib that keeps your baby warm. It also serves as a barrier to drafts and germs.

Other devices help your baby breathe.

- A ventilator is a machine that breathes for your baby while the lungs are growing or healing. It sends oxygen or air into the lungs through a thin tube. The tube is placed in the windpipe through the nose or mouth.

- A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine may be used when a ventilator isn't needed. It gently pushes oxygen or air into the lungs through a mask over the baby's nose or mouth. The baby can breathe on their own with this extra help.

- A nasal cannula is a thin tube with two prongs that are placed in the nostrils when the baby just needs more oxygen. The oxygen goes through the openings in the prongs and into the baby's nostrils. Oxygen may also be given through a clear plastic hood that rests over the baby's head.

Doctors use special tools to give your baby medicine, fluids, and food.

- A medicine pump is a machine that delivers exactly the right amounts of medicines at the right times through an I.V. site, central line, or umbilical venous catheter.

- An intravenous (I.V.) site gives access to a vein. It may be placed in the back of the hand, foot, arm, leg, or scalp. One end of a tube is attached to the site. The other end may be attached to a medicine pump. It can also be used to take samples of blood for testing.

- A central vascular access device (CVAD), or central line, is a long, thin tube that can be placed in the neck, chest, or arm. It is threaded through a vein until it reaches a larger vein near the heart. It can stay in place longer than an I.V. and can deliver fluids or medicines quickly if needed.

- An umbilical venous catheter is a thin, flexible tube. It's inserted into a blood vessel in the belly button (umbilicus). The tube may be attached to a medicine pump.

Other devices help the NICU staff keep track of your baby's condition.

- An inflatable cuff on the arm or leg takes the baby's blood pressure. Then it sends that data to the blood pressure monitor.

- A temperature probe attached to the baby's skin keeps track of your baby's temperature. It can be used to adjust the heat in the isolette or an overhead heater.

- The heart monitor has a sensor attached to the chest. It tracks breathing and heart rate.

- A pulse oximeter clips on to the baby's hand or foot. It measures how much oxygen is in the blood.

You don't have to remember what each piece of equipment does. The NICU staff will answer your questions and tell you how these tools are helping your baby.

It's hard to be apart from your baby, especially when you worry about your baby's condition. Know that the hospital staff is well prepared to care for babies with this condition. They will do everything they can to help. If you need it, ask for support from friends and family. You can also ask the hospital staff about counseling and support.

Your role in your infant's care

If your preterm infant is admitted to the NICU, you'll be an important part of your baby's care team. The NICU doctors and nurses will help you learn about new technologies, medical words, and rules and procedures. They'll show you how to work around the NICU equipment. With their support, you can quickly learn about your baby's needs and what you can do to help.

Physical contact

At first, you may question whether and even how to touch your tiny newborn. Unless your baby is very sick or immature, you'll be allowed to touch and maybe hold your baby.

When you visit your baby in the NICU, remember that:

- A preterm infant has limited energy for recovering and growing. Try not to wake your infant from sleep.

- A preterm newborn's brain isn't quite ready for the world. Be alert to signs that your infant is being overstimulated. These include a change in heart rate or a need to turn away from you. This can be triggered by your gaze, voice, or touch, or by sound and light in the room.

- A stable, more mature preterm baby will thrive on periods of cuddling (kangaroo care), infant massage, and calming music.

Breast milk

A mother can boost her baby's immune system by providing breast milk. Using pumped breast milk for tube-feeding reduces your baby's risk of infection.

Before your breast milk comes in (3 or 4 days after childbirth), you will be asked to decide whether you plan to breastfeed or bottle-feed your baby.

- If you choose to breastfeed, expect to pump milk for feedings until your infant is mature enough to feed by mouth.

- You can provide breast milk for tube-feeding even if you don't plan to breastfeed later on.

Your growing role

As your baby gets stronger, you'll be able to take on more caregiving tasks. These range from holding and feeding to changing diapers and bathing. The NICU nurses will teach you and answer your questions.

If you're breastfeeding, you may be asked to spend the night in the hospital to find out if your baby is strong enough to nurse around the clock.

Learn more

Watch

Taking Your Baby Home

A preterm baby is considered ready to go home when he or she:

- Is able to take all feedings by nipple and keep gaining weight.

- Can maintain body heat in an open infant bed.

- Breathes well. (An infant whose lungs have suffered damage may be sent home with portable oxygen.)

- Has normal breathing and a normal heart rate for a week. (A baby who is otherwise mature enough yet still stops breathing sometimes or has lung disease or other breathing problems may be sent home with a device to monitor breathing.)

Some babies are ready to go home as early as 5 weeks before their due date. Other infants, usually those who have had medical problems, may be sent home later.

Preparing to go home

Here are some important things you can do to get ready for your baby's discharge from the hospital.

- Prepare yourself to care for your baby.

Things to learn include:

- Infant CPR, from a certified instructor.

- How to safely transport your baby in a car.

- How to handle the medicine or medical equipment, if any, that your baby will need at home.

- Basic infant care skills.

- Discuss your concerns.

Share your questions and concerns with the nurses, your baby's doctor, and a discharge planner. A discharge planner can help make sure that your baby will get the right care after leaving the hospital.

- Make follow-up appointments.

Set up an appointment with your baby's doctor for a few days after your infant comes home. Weekly medical checks after discharge are especially important for a preterm infant. They're also reassuring for you.

- Check into home-based services.

If home-based health care and support are available, take advantage of them. These services spare you and your infant the physical and emotional stress of traveling to lots of appointments.

- Get current on your immunizations.

Make sure you're up to date on your vaccines. Ask other people who will be near your baby to be immunized too. It's okay to get routine vaccines while you are breastfeeding. They don't harm your baby.

Learn more

Watch

The First Weeks at Home

As you and your preterm baby adjust to being at home, you will gradually establish a routine together. During the first weeks at home, here are some things to keep in mind.

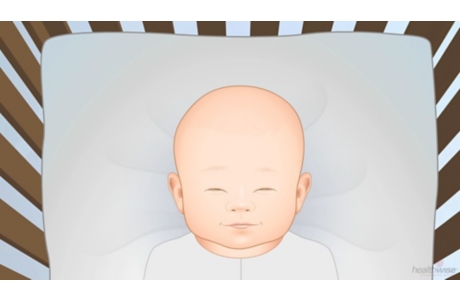

- Sleeping.

Preterm infants' brains aren't as fully developed at birth as a full-term newborn's.

- Preterm infants sleep more than full-term infants do but for shorter periods of time. Expect that you may be awakened often at night until 6 months after your due date.

- They are seldom awake for more than brief periods until about 2 months after their due date. It may seem like a long time before your infant responds to your presence.

- Sleeping position.

Make sure your baby goes to sleep on their back. This lowers the chance of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). SIDS is more common among preterm babies than full-term babies.

- Fussiness and sensitivity.

It's normal for full-term infants to cry for up to 3 hours a day by 6 weeks after their due date. Most premature infants will do the same and then some.

Your premature infant may be easily disturbed by too much light, sound, touch, or movement or even by too much quiet. If so, gradually create a more calming environment. Swaddle your infant in a blanket, and hold them as much as you can.

- Feedings.

Your baby probably will come home with a hospital feeding schedule, which will tell you how often to nurse or bottle-feed at home.

- To avoid dehydration, never go longer than 4 hours between feedings.

- Small feedings may help reduce spitting up. If you see signs of reflux during or after feedings, such as spitting up a lot, talk to your infant's doctor.

- Nutrition.

Your baby's doctor may recommend adding iron, vitamins, or formula to a breastfed diet.

- Adding iron is a common treatment. Preterm infants lack the iron stores that full-term infants have at birth.

- Some preterm babies simply need extra energy and vitamins from formula (along with breast milk) to keep up their growth.

- Disease prevention.

Preterm babies get sick more easily than full-term infants. So make sure your baby gets regular checkups and recommended immunizations to protect against serious illness.

- With the exception of the hepatitis B vaccine, a preemie's immunization schedule is the same as for a full-term infant, figured from the date of birth (chronological age).

- The doctor may also suggest that your baby get injections of RSV antibody in the winter. This may help reduce the risk of problems from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

To help protect your baby:

- Be current on your immunizations. Ask other people who will be near your baby to be immunized too.

- Keep your baby away from sick family members and friends.

- Avoid group child care if your baby is at high risk for infection. This is most important in the fall and winter when viral illnesses tend to spread.

- Don't let anyone smoke near your infant.

- Hearing and vision screening.

Premature infants are at greater risk of hearing loss. Your baby's hearing will be checked in the hospital. But be alert to new or increased hearing problems during your child's first 5 years of life.

Babies born at or before 30 weeks or weighing less than 1500 g (3.3 lb) are more likely to develop a vision problem called retinopathy of prematurity. Vision screening is recommended for these babies and for those who have serious medical conditions. The first screening is recommended between 4 and 9 weeks after birth.footnote 1

Learn more

Watch

Looking Ahead to the Childhood Years

Your infant's 'age'

It can be helpful to understand your preterm baby's corrected age. This is how it's figured.

- Chronological age is measured from the day of birth. Birthdays are celebrations of a child's chronological age.

- Corrected age is your child's chronological age minus the number of weeks or months the child was born early.

For example, if your 1-year-old was born 3 months early, your child's corrected age is 9 months. You can expect your child to look and act like a 9-month-old.

Knowing your child's corrected age may be reassuring as you follow your child's growth and development.

Your infant's development

Your child will reach the same growth and development milestones as other children. During the first 2 years of life, your child may seem to reach these milestones later than full-term children of the same age. But this is because your child was born early. Your child will catch up around age 2.

When your child starts school, be alert for signs of learning problems. Problems with learning, reading, and math due to preterm birth may first show up during the early school years.

Learn more

Related Information

- Breastfeeding

- Chronic Lung Disease in Infants

- Crying, Age 3 and Younger

- Dealing With Emergencies

- Growth and Development, Newborn

- Hospital Discharge Planning

- Jaundice in Newborns (Hyperbilirubinemia)

- Medical Specialists

- Music Therapy

- Preterm Labor

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Support Groups and Social Support

Credits

Current as of: October 24, 2023

Author: Healthwise Staff

Clinical Review Board

All Healthwise education is reviewed by a team that includes physicians, nurses, advanced practitioners, registered dieticians, and other healthcare professionals.

Current as of: October 24, 2023

Author: Healthwise Staff

Clinical Review Board

All Healthwise education is reviewed by a team that includes physicians, nurses, advanced practitioners, registered dieticians, and other healthcare professionals.

Topic Contents

- Overview

- Health Tools

- Delivery of Your Preterm Infant

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Health Problems in Preterm Newborns

- Treatments a Preterm Infant May Need

- Getting to Know the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

- Taking Your Baby Home

- The First Weeks at Home

- Looking Ahead to the Childhood Years

- Related Information

- References

- Credits

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.